Roland

Barthes

Many of Barthes’s works focus on literature. However, Barthes denied being a literary critic, because he did not assess and provide verdicts on works. Instead, he interpreted their semiotic significance. Barthes’s structuralist style of literary analysis has influenced cultural studies, to the chagrin of adherents of traditional literary approaches.

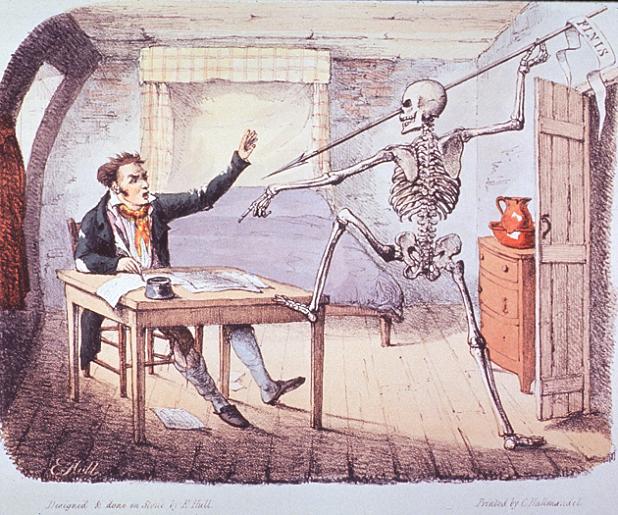

One notable point of controversy is Barthes’s proclamation of the ‘death of the author’. This ‘death’ is directed, not at the idea of writing, but at the specifically French image of the auteur as a creative genius expressing an inner vision. He is opposing a view of texts as expressing a distinct personality of the author.

Barthes vehemently opposes the view that authors consciously create masterpieces. He maintains that authors such as Racine and Balzac often reproduce emotional patterns about which they have no conscious knowledge. He opposes the view that authors should be interpreted in terms of what they think they’re doing. Their biographies have no more relevance to what they write than do those of scientists.

In ‘The Death of the Author’, Barthes argues that writing destroys every voice and point of origin. This is because it occurs within a functional process which is the practice of signification itself. Its real origin is language. A writer, therefore, does not have a special genius expressed in the text, but rather, is a kind of craftsman who is skilled in using a particular code. All writers are like copywriters or scribes, inscribing a particular zone of language.

The real origin of a text is not the author, but language. If the writer expresses something ‘inner’, it is only the dictionary s/he holds ready-formed. There is a special art of the storyteller to translate linguistic structures or codes into particular narratives or messages. Each text is composed of multiple writings brought into dialogue, with each code it refers to being extracted from a previous culture.

Barthes’s argument is directed against schools of literary criticism that seek to uncover the author’s meaning as a hidden referent which is the final meaning of the text. By refusing the ‘author’ (in the sense of a great writer expressing an inner brilliance), one refuses to assign an ultimate meaning to the text, and hence, one refuses to fix its meaning.

It becomes open to different readings. According to Barthes, the unity of a text lies in its destination not its origin. Its multiplicity is focused on the reader, as an absent point within the text, to whom it speaks. The writer and reader are linguistic persons, not psychological persons. Their role in the story is defined by their coded place in discourse, not their specific traits.

A text cannot have a single meaning, but rather, is composed of multiple systems through which it is constructed. In Barthes’s case, this means reading texts through the signs they use, both in their structure in the text, and in their wider meanings.

Literature does not represent something real, since what it refers to is not really there. For Barthes, it works by playing on the multiple systems of language-use and their infinite transcribability – their ability to be written in different ways.

The death of the author creates freedom for the reader to interpret the text. The reader can recreate the text through connecting to its meanings as they appear in different contexts.

In practice, Barthes’s literary works emphasise the practice of the craft of writing. For instance, Barthes’s structuralist analysis of Sade, Fourier and Loyola emphasises the structural characteristics of their work, such as their emphasis on counting and their locations in self-contained worlds. He views the three authors as founders of languages (logothetes).

Death of the Author

By Andrew Robinson

http://www.printfriendly.com/print?url=http%3A%2F%2Fceasefiremagazine.co.uk%2Fin-theory-barthes-4%2F&partner=a2a#